Pathology of Female Reproductive System: Key Disorders and Treatments

Lesson Overview

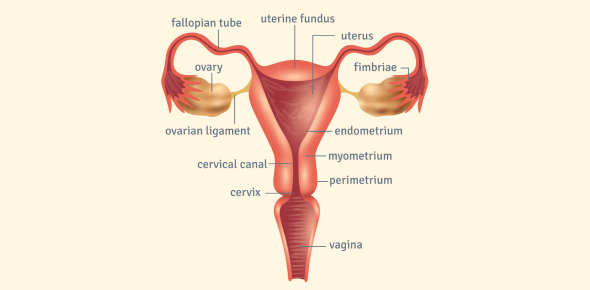

The female reproductive system spans multiple organs (vulva, vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries), each with unique pathological disorders. These pathologies range from benign growths and inflammatory conditions to precancerous lesions and malignant tumors. Understanding the major disorders and why they arise is crucial for recognizing clinical presentations and implications.

In the sections below, we explore key disorders of the female reproductive tract in a structured manner-starting from developmental anomalies and moving through external genital lesions, cervical neoplasia, endometrial changes, and infection-related complications.

Vulvar Lesions: Leukoplakia and Related Disorders

The vulva can exhibit lesions that appear as white patches or plaques (leukoplakia). Leukoplakia is a descriptive clinical term for any white vulvar plaque; it is not a diagnosis itself, but a sign that prompts biopsy to determine the cause. Key vulvar conditions include:

- Lichen sclerosus: A chronic inflammatory condition, typically in postmenopausal women, causing thin, white, parchment-like vulvar skin with intense itching. Over time it can slightly increase the risk of squamous cell carcinoma due to chronic inflammation.

- Lichen simplex chronicus: Reactive thickening (hyperplasia) of the vulvar skin from chronic scratching or rubbing. It presents as a leathery, white, itchy plaque. This change is benign and not premalignant – if the irritation stops, the skin can return to normal.

- Condyloma acuminatum: Genital warts on the vulva caused by low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6 and 11. They appear as multiple cauliflower-like growths. Histology shows papillary fronds and koilocytes (haloed squamous cells with viral changes). Condylomas are benign with minimal risk of malignant transformation.

- Extramammary Paget disease: A rare adenocarcinoma in situ of the vulvar epidermis, usually in an older woman. It presents as a chronic, red eczematous patch with itching or burning. Paget cells (malignant glandular cells) are scattered within the epidermis. Unlike Paget disease of the breast, the vulvar form typically has no underlying invasive carcinoma. The lesion tends to persist or recur unless widely excised.

- Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: The most common vulvar malignancy. It may present as an ulcer, nodule, or warty mass. Two pathways: one is HPV-associated (via a precancerous stage called vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, VIN, often in younger women), and the other is HPV-independent (often in older women with long-standing lichen sclerosus or inflammation). Vulvar SCC can invade locally and spread to inguinal lymph nodes if not caught early.

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) and HPV

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is a spectrum of precancerous changes in the cervical squamous epithelium caused by persistent infection with high-risk HPV (especially types 16 and 18). HPV's oncogenic proteins (E6 and E7) disable tumor suppressors (p53, Rb), which explains how the virus leads to dysplasia. CIN is graded by how much of the epithelium is affected:

- CIN 1 (Mild Dysplasia): Abnormal cells in the lower one-third of the cervical epithelium. This often indicates a transient HPV infection and is considered low-grade. In young women, CIN 1 often regresses on its own.

- CIN 2 (Moderate Dysplasia): Abnormal cells extend into the middle third of the epithelium. This high-grade lesion has a significant risk of progression if untreated, so CIN 2 typically warrants removal of the abnormal tissue.

- CIN 3 (Severe Dysplasia / Carcinoma in situ): Abnormal cells occupy more than two-thirds of the epithelium, up to full thickness. Carcinoma in situ means the epithelium is completely replaced by dysplastic cells with no invasion beyond the basement membrane. CIN 3 is essentially the final stage before invasive cancer.

In Pap smear screening, low-grade lesions (CIN 1) correspond to LSIL, whereas high-grade lesions (CIN 2 and 3) correspond to HSIL. Progression from CIN 1 to higher grades usually requires persistent high-risk HPV over several years. Regular Pap smears allow early detection of dysplasia. A high-grade Pap result (e.g. HSIL or ASC-H) warrants colposcopic examination and biopsy to locate and treat any CIN 2/3 before it can progress to an invasive carcinoma.

Pap Smear Cytology Terms

A Pap test examines cervical cells. Common abnormal findings include:

- ASC-US: Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance – mild cell atypia with uncertain cause (could be benign reactive changes or mild dysplasia). Usually followed by a repeat Pap or HPV testing.

- ASC-H: Atypical Squamous Cells – cannot exclude HSIL – some cells appear suspicious for a high-grade lesion. This finding calls for immediate colposcopy and biopsy, since CIN 2 or 3 might be present.

- LSIL: Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion – indicates mild dysplasia, usually due to HPV (often correlating with CIN 1). Many LSIL lesions will regress on their own, especially in younger patients, but persistence should prompt further evaluation.

- HSIL: High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion – indicates moderate to severe dysplasia (CIN 2 or 3). There is a high risk of progression to invasive cancer if not treated. This result requires prompt biopsy and usually excisional treatment of the affected area.

Endometrial Hyperplasia and Histological Features

Excess estrogen stimulation on the uterine lining (without the balancing effect of progesterone) can cause endometrial hyperplasia – an overgrowth of endometrial glands. This often occurs with chronic anovulation (e.g. polycystic ovary syndrome or perimenopause), estrogen-secreting tumors, or unopposed estrogen therapy.

Endometrial hyperplasia is concerning because it increases the risk of endometrial carcinoma, especially when atypical cellular changes are present. Pathologically, hyperplasia is categorized into two main types:

| Endometrial Hyperplasia | Microscopic Features | Atypia? | Cancer Risk |

| Without atypia (simple or complex) | Proliferation of glands with an increased gland-to-stroma ratio. Glands may be dilated or irregular, but the cells are cytologically normal (no nuclear atypia). | No | Low (rarely progresses to cancer) |

| With atypia (atypical hyperplasia) | Crowded, back-to-back glands with little stroma, plus nuclear atypia in the glandular cells (enlarged, irregular nuclei). This is essentially a precancerous lesion (also called endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia). | Yes | High (significant risk of concurrent or future endometrial adenocarcinoma) |

Clinically, endometrial hyperplasia usually presents as abnormal uterine bleeding – for example, heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding, or bleeding after menopause. The why is that unopposed estrogen keeps the endometrium growing when it should be shedding, leading to an overly thick, fragile lining. An anovulatory cycle is a common example: if ovulation (and thus progesterone) doesn't occur, the endometrium stays in a prolonged proliferative state and can become hyperplastic. Hyperplasia with atypia is often managed aggressively (e.g. surgery) due to its high progression rate to carcinoma.

Müllerian Duct Anomalies

Müllerian duct anomalies are congenital malformations of the female reproductive tract due to errors in embryologic development of the Müllerian ducts. Normally, two Müllerian ducts fuse into one uterus and the dividing septum then dissolves to form a single uterine cavity. Mistakes in these steps lead to common anomalies:

- Failure of duct fusion: If the two Müllerian ducts do not fuse, a divided uterus results. Complete non-fusion yields a uterus didelphys (two separate uteri, two cervices, and often a duplicated vagina), whereas partial fusion failure produces a bicornuate uterus (a single uterus with two horn-shaped cavities at the top). These anomalies effectively split the uterine space, leading to recurrent miscarriages or preterm births because each cavity is smaller and less optimal for fetal development.

- Failure of septum resorption: If the ducts fuse but the internal partition fails to resorb, a septate uterus is formed. In this case, a fibrous or muscular septum divides the uterine cavity into two. A septate uterus also causes infertility and miscarriage risk, since an embryo implanting on the septum (which has poor blood supply) is likely to fail. Unlike a bicornuate uterus, a septate uterus can be treated by surgically removing the septum to create a normal single cavity.

Both bicornuate and septate uteri create suboptimal environments for pregnancy (due to divided cavities), which is why they lead to reproductive difficulties. Distinguishing between them via imaging is important, as a septum can be removed to improve outcomes, whereas a bicornuate shape cannot be surgically unified.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) and Gonococcal Infection

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease is an infection of the upper female genital tract (uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries) usually caused by sexually transmitted bacteria ascending from the cervix. The most common culprits are Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. PID typically presents with lower abdominal pain, fever, adnexal tenderness (pain on cervical motion), and purulent cervical discharge. Key pathologic consequences of PID include:

- Salpingitis: Inflammation of the fallopian tubes is the hallmark of acute PID. The infected tubes may fill with pus (pyosalpinx), and the tubal lining is damaged by neutrophilic inflammation. Severe cases can progress to a tubo-ovarian abscess if infection involves the ovary and surrounding tissues.

- Scar formation and infertility: As the infection heals, scar tissue and adhesions form in and around the fallopian tubes. This scarring is why PID often leads to infertility – blocked or distorted tubes prevent normal fertilization or transport of the egg. It also greatly increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy later on, because a fertilized egg can become stuck in a scarred tube and implant there instead of in the uterus.

- Chronic pelvic pain: Persistent adhesions in the pelvis after PID can tether organs together, leading to ongoing pelvic pain long after the acute infection has resolved.

Early antibiotic treatment of gonococcal or chlamydial infections can prevent the severe damage that leads to these complications. Once scarring has occurred, the effects (infertility, ectopic pregnancy risk, chronic pain) are often permanent, underscoring the importance of prevention and prompt treatment.

Rate this lesson:

Back to top

Back to top

(93).jpg)